The body of Oluwatoyin “Toyin” Salau, a 19-year-old Black Lives Matter activist, was found on Saturday night around 9:15 p.m. on Monday Road in southeast Tallahassee, Florida. According to reports, Salau was a victim of kidnapping and homicide along with 75-year-old Victoria Sims, a former local politician and AARP volunteer. Root.com reports that 49-year-old Aaron Glee Jr. is in custody for the murders and kidnapping of both women. Details on this case are forthcoming.

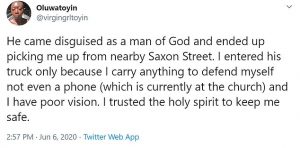

Salau had been missing since June 6th, the same day she tweeted a thread of her sexual assault survival story. Salau said in her tweets that she was given a ride by a man who offered to help her collect her belongings from a church where she had been staying in order to “escape unjust living conditions.” The man then assaulted Salau in his home, which she subsequently reported to police. According to the Orlando Police Department the description of Salau’s attacker does not match that of the homicide suspect Aaron Glee Jr.

There has been an outpouring of grief over Toyin’s murder with some celebrities, like Gabriel Union and Kerry Washington, expressing their thoughts on her untimely death on their social media pages. Many people have shared photos of Toyin to celebrate her memory. But one of the most compelling moments of her life has resonated with a lot of black women. It is a video of Toyin speaking at a protest over the murder of Tony McDade. In the video Toyin proclaims that the movement and protests should be for every single black person—including black queer individuals like McDade. She asserts that our black skin cannot be removed, and we do not deserve to be profiled for it. Eerily she says regarding her skin and her black identity that, “I’m a die about it.”

This is the ideal point at which I would pivot the conversation to highlight the growing concerns for overlooked members of the black community and why Toyin was justified in saying that she advocates for “every black person.” I would provide data to underscore the harsh realities—the rising number of black trans murders, the over 64,000 missing black women and girls, the over 40% of black girls who report being sexually assaulted before age 18—I would list it all, contextualize it, and call for change.

I would then connect all of this to Toyin. I would insist that she was the embodiment of the statistics we often gloss over. She wasn’t a number, but a person who had actually lived the kind of existence we pretend doesn’t happen to many of us. A woman completely and totally unprotected by every single person around her. A woman embracing her black identity and fighting for the right of others to do the same. A woman abused, traumatized and then murdered in her prime. This was a life. This was a human being. Welcome to the black female experience.

Have a seat, we need to talk. The reason I will not list statistics is because no one cares about them. No one cares about black lives, this is why there is a movement. Somehow the numbers make us care even less. We can disassociate because the numbers don’t seem real and we don’t know any of these people personally.

Moreover, the numbers make the problem seem insurmountable. We have more questions than answers; more happening behind the scenes than we can even imagine. Does this then make the black female struggle also seem insurmountable? Furthermore, are we afraid to talk about this because it implicates black men as a part of that struggle?

This is an extremely complex, multi-layered matter. Attempts at finally having this very important dialogue have been suppressed by people who think it “distracts from the movement” or that we should “stop arguing and stick together”. I agreed with some of these sentiments initially, but then I questioned why I thought black female issues are a distraction. Especially since I face some of these issues daily.

At the height of the protests in Philadelphia I was asking people around me to make sure I went along with them for any errands or store runs for their protection. Men included. I would say, “they won’t harass you too much if you’re with a woman.” Now I think to myself, what kind of protection was I going to provide. My height? But at any rate, I was ready for the sacrifice; I didn’t even think twice about it. And I did this with the knowledge that black women often get publicly mistreated the same way that black men do.

But I have convinced myself, as many of us have, that I am actually less vulnerable than black men. And no one believes this more than black men. They read our strength as a foundational to our identity. There is no black woman that is not strong; and the darker your skin somehow the stronger you are. I did not make this up. Indeed, there is a spectrum: the closer you are to appearing white, the more vulnerability you are afforded. But the girls at the darker end of that spectrum—we are left out here to dry.

And we are aware of this. Black girls are aware they have no space for fragility. I would argue that we are hyper aware. The moment our guard is let down it could literally cost us our life, our children, our home, our job, our partner. We are the backbone of the race, and we accept this challenge willingly.

This strong black woman stereotype has been both romanticized and denigrated. Its functioned well enough to result in our defeminization. We cannot tackle black female issues if we have defeminized the black woman. So what we do instead is correlate the concerns of black women with that of black men because we have 1. convinced ourselves black women are strong enough to handle their own problems 2. convinced ourselves that black women are an extension of black men and share the exact same problems.

We are socialized to think this way about black women and the race as a whole. People believe that only white people are socialized to be anti-black. But the truth is we are all socialized to be anti-black. Black people are anti-black. A lot of them. Some of them are even in your family. You may even be anti-black. Anti-blackness is global, and deeply entrenched in our understanding of the world. We blame black people for black problems and black subjection. And what’s troubling is we have no idea that we are doing this. We have no idea that our perspectives have been framed by anti-black sentiments. We simply explain issues away with the same rhetoric that white people use: “he was a criminal he deserved to die”, “well she was being loud and ghetto”, “well if he complied with the police he would be alive today.”

We struggle to confront our anti-blackness, especially when it concerns black women. We think because we are black we cannot be anti-black. But the truth is we have internalized and accepted racialized misconceptions of black people and the black woman. And its scary to unpack that for many of us. Because then we may realize that we are in fact anti-black. And since black women are so deeply connected to blackness because of long held prejudices, then silencing black female voices in the movement is actually the way we show we are most anti-black.

And of course, there are long held prejudices of the black man as well. I am not condemning us or dismissing any one groups’ concerns. But I am making the claim that distancing ourselves from the black woman and the issues that concern her is the way we manifest our anti-blackness. This is connected to the conversations on dating preferences, black women’s hair, black female athletes, black women’s medical experiences, and yes the movement. If you find yourself making a concerted effort to put space between yourself and these issues, you may be anti-black.

I am asking us to challenge our preconceived notions of each other, have the dialogue, and meet each other halfway. Black female voices need to be heard in this movement, they deserve justice and our attention. Toyin deserved our attention.

Toyin should be here today. She had her entire life ahead of her and a future that was certainly bright. I wish she was allowed to be free in a world that only sought to destroy her. I hope that her story helps us to understand that there are many girls like her: young, vulnerable, preyed upon. Let us protect and nurture them. They deserve to be cherished.

I hope Toyin rests in eternal peace. Her short life has made a difference; her story will change futures.

#Sayhername